Finding myself…

The 3:22:54 Honiton Marathon proved I could survive the distance. I knew the fabled ‘wall’ only required proper training and a good diet to ease through. In 5 months I’d gone from smoking, non-runner, to a non-smoking marathoner. Running had grabbed me. Now I needed to find out if I could run faster and figure out a way to do so. In late 1982, I was looking for a spring marathon to aim for. I had also decided to coach myself. I was obsessed with all the magazines and books available, and digested everything. Still using Berni Mundy’s initial schedule as a model, I drew up a plan which could get me to run below 3:15:00. In truth, I wasn’t absolutely sure what I was doing – I was lacking the full understanding as to each training affect, and the combined effects on my body. It was like online learning, without the internet – I had to read, talk, listen and absorb facts, then try to place things in a logical order. I was my own experiment.

As 1982 drifted towards winter, Wednesday nights with the Harriers became very important to me. Shift work meant I missed some of these, and also meant I was a lone trainer. Club nights gave me a social life and the chance to test my fitness against naturally quicker runners. As I said in my first blog, I’m not built like a Ferrari. I’m more of a JCB-GT, and as elegant as a bag of spanners. I’m more of a sprinter in physique. I had won the Area Sports 100m when I was twelve years old in 12.2 seconds; at thirteen I ran 11.9 seconds – all of this in bare feet on grass as we couldn’t afford footwear. With no encouragement, I stopped any activity at 15 years old.

Some of the Harriers were just plain rapid, long legged and ran effortlessly. However, at the time, unbeknownst to me or anyone else, my naïvety meant was training harder than most. No one had yet to tell me I was getting it wrong. To make even less sense, in getting it wrong, I was still improving – but the hard way. My body was adjusting to a war of attrition. I also noticed that I was taking things far more seriously than my club mates. My antisocial job and solo running underpinned the fact that I’m introverted in my focus, though extroverted in execution. My bleak childhood had given me an inner rage formed of doubt and lack of love. I trained to feel good about myself – rarely with anyone else. I raced with a passion and loved interaction with my fellow Harriers. (43 years later, I’m very much the same – running is a daily part of who I am and I train alone. Interaction in races, or meeting other runners gives me great pleasure and happiness.)

Without a marathon date for 1983, I had yet to start following my own schedule, so, after Honiton, I just ran around 40 miles per week in my usual hell-for-leather style. In hindsight, I think I was addicted to the pain of effort and post-run glow. (I have never felt worse after a run, ever.) For the seven weeks from the end of October to the third week in December I ran 6 x 10 milers and 3 x 12 milers as long runs. I can find no runs where I dropped below 7:15 pace. My shortest runs were 5 milers! It is hardly surprising that my calf muscles were starting to hurt. Then, on Saturday 18th December 1982, I received a London Marathon acceptance letter…

Coaching myself…

The schedule I drew out was pretty tough. I was determined to get down to hard work immediately, but the brutal way I was knocking myself into shape was starting to work against me. My inner, right calf, probably my Achilles tendon, was not just hurting, but was excruciating. Still, I ran a 1:03:21 ten miler on Christmas Eve and the tendon held out. (I measured all my routes with the edge of paper and an OS map. I just checked a couple of my old routes on Mapometer and they are all no more than 100m out either way – this ten was almost spot on.)

The week up to 1st January 1983 I completed 46 miles, including a 12 and 14 miler! Then, disaster. I couldn’t put weight on my right leg to run. I set out on a 10 on the 3rd January, but the pain in my Achilles was agony. I couldn’t run. (I’m still the same: I have to be physically incapable, not to run.) I didn’t run for nine long days. I iced my tendon, rested it as best I could, but still cycled to work and hoped I would repair quickly. It was my first experience of an injury.

On 11th January I ran an ‘easy’ 5 at 7 minute miles – the tendon felt better! I ran with my brother, Pete, and also with my young pal and Harrier, Stewart Cox. Stewart ran with me for 1:09:48 and a 1:04:38 ten milers to get 50 miles in the following week. If Stewart wasn’t training, I found other hard running Harriers to train with – these runs were always fast. My preferred solo running meant I would not push so hard. I was back in the groove and completed five full weeks of training, including a 16 mile long run.

The rigid schedule I’d produced was too hard, so I began to drop the occasional run if I was exceptionally tired. I had rest days built in, too. So, my first lesson in self-coaching was to view rest as essential – not a weakness. Yet, I still to this day find rest a discipline. Also, the reason I was running with different Harriers, was because no one trained as intensely as I. Stewart would run hard with me, then rest. As would the others. I was not learning quickly enough. Something had to give…

wearing our London medals

One flu’ over the cuckoo’s nest…

Cycling to work, 6 miles each way, 6 days on, 2 days off, on shifts continued. The twins were 6 now. My wife and I were full on in the house and parenting department. How I fitted in the running is beyond me now. I was only 26 and sacrificing rest to fulfil all my duties as daddy and husband.

On the last of six night shifts on Sunday 13th February I felt unwell. Something was not right. I cycled home on the Monday and went to bed. I remember it well. I woke up and the room was spinning, my throat was dry and my heart felt like it was trying to leave my chest. Fear. I got up and had to hang onto the door as I couldn’t see! My head was unconscious but somewhere I could still function. I called my wife. She rushed up the stairs and helped me back into bed.

“You’ve got flu!” She said.

I’m not one to give in to colds, but I’d never had flu’. I discovered it was very frightening. (I’ve only had it a few times since – I now have the jabs.)

I didn’t run for 11 days. Then, looking gaunt and weary, I set out on a 5 miler and ran just under 37 minutes, feeling ‘tired and weak’. By the end of February, I had tried to claw back my lost training in the usual fruit-loop way, knocking out 6 x 10 milers, and a 14, 16, 18 and 20 miler in March alone! My shortest run was a 5, and 4 x 6s, every other run was 8 miles plus. No run was slower than 7:30 pace. Looking back, this was an insane amount of effort. All I can say is that I was addicted to holding those faster paces in a sort of dream state. Runners high? Possibly. It was so new, so vivid and my body reacted positively to the demands I set on myself. My fellow Harriers regarded me askance, wondering how I didn’t fall to pieces. Being slightly embarrassed, I never told them about every run I was doing. I’d drifted back to manic training. I was still getting it right, by getting things wrong. There had to come a point where my training needed some clear plan.

I tapered for London. Well, sort of. Two weeks before I ran 20 miles in 2:19:03. The following day I cycled from my home in Highbridge, over the moors, over the Mendip Hills via Cheddar Gorge, to Chew Valley Lake, to watch birds! In total I covered 55 miles, with two huge climbs. I didn’t run when I got home, writing, “Went to Chew Lake today and chose to rest – legs OK, no problems.” I didn’t count cycling as training in those days… That penultimate week I ran 46 miles. The week before the marathon I ran a 68 minute 10 miler, then a 6, 5 and 4… then rested for 2 days.

I travelled to London by train with my brother, Pete, on the Saturday. I knew very little about London, then. So we’d booked onto a cheap hotel just off the Bayswater Road. At the pre-race expo, I picked up my number, 4839, bimbled about then I seem to remember eating some spaghetti somewhere, before going back to our hotel and realised I’d done something daft. In those days the tube never ran until 09:00 on Sundays! I had to get to Charing Cross Station by 07:00, to catch my train to the Blue Start at Blackheath. I had no money for a cab, and buses were not running at that time on a Sunday, either. What to do…

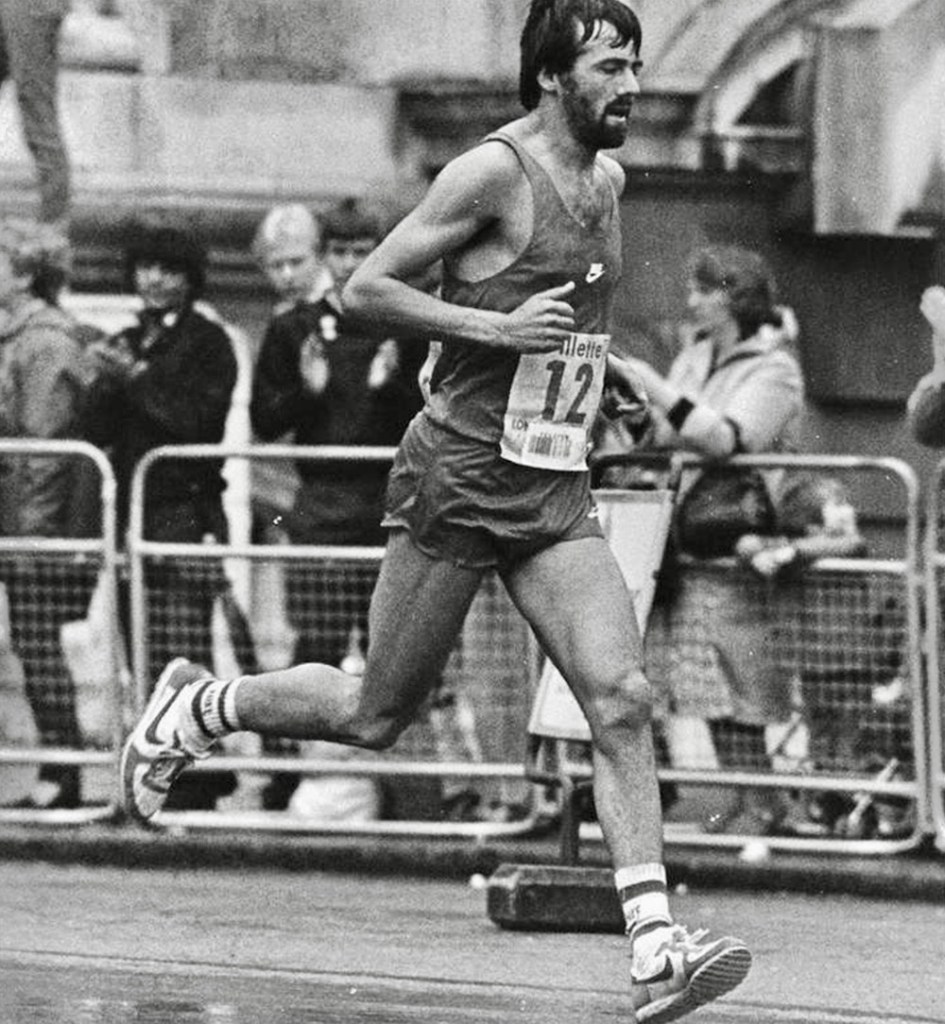

Sunday 17th April 1983 – London Marathon

At 06:00 on marathon morning, I was out in the chill air walking the 2½ miles to Charing Cross. I carried my belongings in a small kit bag. The station was packed, as were the trains, but I got to Blackheath on time and was keen to ditch my bag onto the allocated bus, which would park near the finish at the Jubilee Gardens by County Hall, home of Ken Livingstone’s GLC.

From my Running Log (with minor edits):

‘A couple of cups of coffee went down well, but the rain started at 08:00 and made it uncomfortable to change. I decided to wear my half-mesh vest, with my Ron Hill shorts, checked the laces on my shoes, and put on a bin-liner to keep me dryer. Bag onto the bus and I got onto the road, ready to start.

We surged forward and, with a cheer, the happy sea of humanity started their watches when the canon boomed. It took me 1:05 to reach the official start line [no chip timing then, so one had to deduct the time to the start from the ‘official’ finishing time.] The first mile was painfully slow and I was a little frustrated at passing the marker in just over 10 minutes [which, of course was about 08:55, in reality.]

After this the pace of the mob increased, with minor holdups at the early feed stations. As the crowd eased and I found space, I started running quicker, but well within myself, and reached 10 miles in a shade over 1 hour 14 minutes. I felt this was slow, but was loving the crowds and fellow runners happy energy.

Seeing Tower Bridge was a boost, and my halfway split was around 1 hour 34 minutes. I was fairly settled around the Isle of Dogs, hoping I was not trying to reduce any deficit in my hoped-for time too quickly. Yet, I felt comfortable enough, the atmosphere was incredible and the experience, one to savour.

17, 18 and 19 miles passed. I was intent on that 20 mile split – 2:24:30 – well up on Honiton, but slower than I would have liked. [I knew I was slower than I was capable of running, but settled for my target pace – that was (probably) sensible.] From 22 miles the going got tough. I was feeling ‘the wall’ at this faster pace. My legs got very heavy and the next couple of miles were very hard work.

The London crowd were great and that support helped me no end. I’d never experienced anything like it. The cobbles at the Tower of London were heavy going, but the sight of Waterloo Bridge gave me heart, and the crowds kept my head from dropping. By 24 miles I’d hit my lowest point, far different than Honiton, and the next mile was a real bummer. It was the first time I’d experienced such tiredness since I started running.

Then I turned into The Mall, saw the 25 mile marker with Buckingham Palace beyond. The huge scale of the city and the wide roads seemed to pull me down, the gravity stronger. Yet, as I turned into Birdcage Walk I knew I’d make it. My legs were moving easier. Quicker. In short succession I saw 3 fellow runners keel over – ‘splat!’ – really distressing to see. I learnt a lot about the capricious nature of running a marathon at that point, so close to the finish. It made a big impression on me.

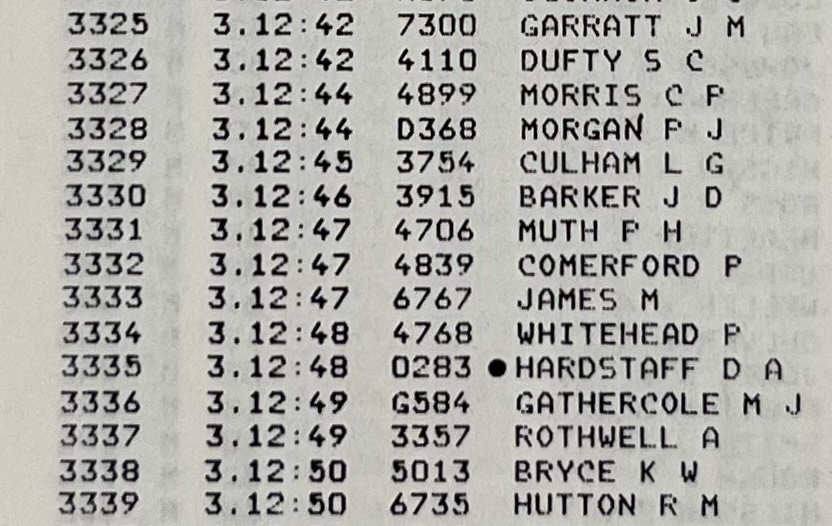

Up ahead I could see Westminster Bridge, so I focussed, pushed hard and was lifted by Pete yelling me on by Big Ben! Faster now, I ran hard to the end, stopping the clock at 3:12:48. In fact, my real time was 3:11:43. Over 11 minutes quicker than Honiton! About 7:18 pace. I was very pleased.

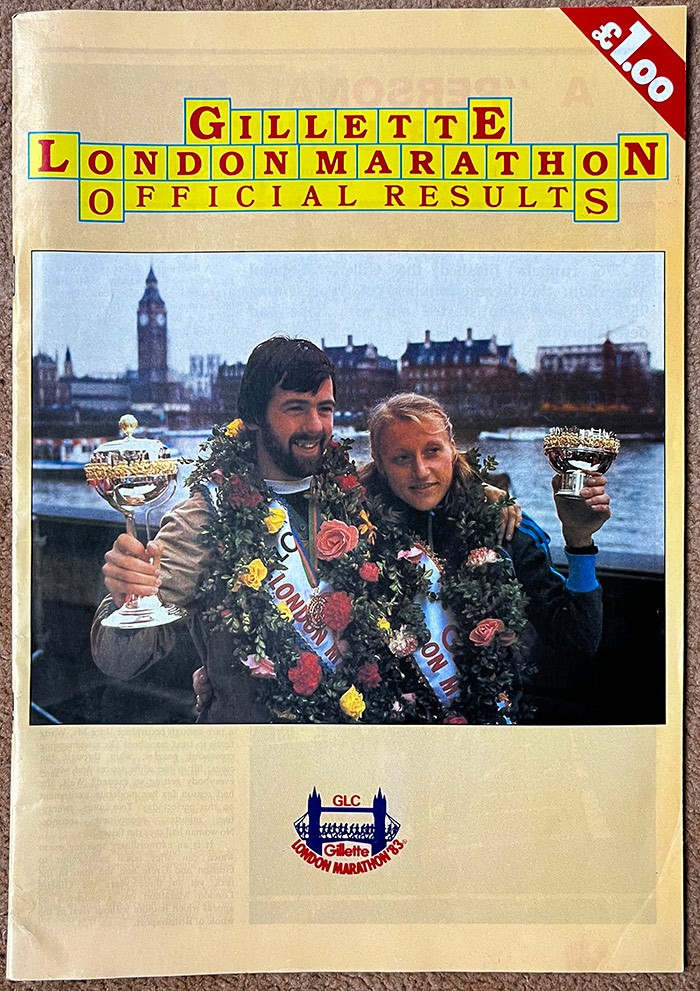

Mike Gratton won the men’s race in a brilliant 2:09:43 and Grete Waitz equalled the women’s world record of 2:25:29!…

… What next? Well, the North Kent Marathon in September, then a return to Honiton in October – I believe I can get close to 3 hours, by then. The marathon holds a strange fascination for me.

Later, my wife and son, Glenn’s, voices over the phone rounded off my day. Now, all I want to do is go home…’

It was odd reading this last part again. My twin boys, Iain and Glenn, were 6 then. Glenn died in 2024. Writing these retrospective blogs takes me back to things I’d forgotten. Happy, magic moments. It does me no harm. It underlines the trail I’ve taken to now. Grief and strength balances out the emotional confusion. The strength comes because I’m still fascinated by life and running, now with distances beyond the marathon. Running helps me cope. It helps me deal with the rage and grief I carry. It makes me kinder and wiser, I hope.

After London 1983, I knew I had to structure my training. I was doing the same thing I had since I’d started running, less than a year before – running hard and hoping. I was literally mixing speed, tempo, strength and endurance training into every run. I needed to understand myself, and thereby find myself. I had to take things seriously, oddly enough, by not being so rigidly serious. Seriously. If I did, could I get near to 3 hours in autumn 1983?

on the cover of the results booklet

My stats:

Time: 3:11:43

Position: 3332

Pace: 7:18

Tips from an Ancient Harrier – No.3: Feet, socks and shoes

Feet – If you run a long way the most important part of your body, is your feet. In a recent 50k I took over 70,000 steps! Even if you end up walking, or staggering, you’ll still be on your feet. Understand them, know the mechanics, and treat them well. I keep my toenails very short and walk barefoot around the house, even in winter.

Socks – After over 41,000 miles of running, I find Injinji toe socks perfect to stay blister-free. Only once in the last three decades, on a 32-mile hot, hilly trail run, have I developed a tiny blister, and that was due to changing shoes and allowing a small speck of grit in. Injinji’s are not cheap, but last for years and are worth the investment. Blisters should be viewed as a rarity, not a badge of honour. (Ultramarathons beyond 50k become a grey area, but keep to the plan and severity is much reduced.)

Shoes – Never skimp on shoes. Ever. Always ensure they fit comfortably. If they feel wrong out of the box, they will not get better. Always use the right shoe for the right surface. Road shoes on trails are okay, but the higher heel may cause you to trip more often. A 5mm or 6mm drop is better as it lowers the heel and ‘lifts’ the toe and jaggedy rocks are more easily missed. Choose a brand that suits you. In my case, after years of trying most brands, I settled on Hokas. (I’ve got far too many, but why not?) For the road, Cliftons are great for comfort, training and racing. Bondi for long road runs. ATR Challengers are superb for road/trail mixed surfaces. Speedgoats for trails only (but are fine on sections of road). I’m now eying their Mafate and Tecton models for long trail ultras.

The triple clean

- Know your feet intimately. Keep your feet clean and healthy. I even moisturise mine. If you think feet are ugly, then give them a beauty treatment and keep them lovely. Love your feet.

- Wash your socks in non-bio, without conditioner (use Dettol Laundry Sanitiser occasionally) and don’t knock the hell out of any technical, synthetic garment in a dryer – ever.

- Clean your shoes regularly. Surface clean with a soft brush and something like Grangers tech detergent. Remove the insoles to wash them. Dry in the sun, or open air when you can. Even wash the laces – seriously – you can dry them flat and your shoes will look new.

All website content ©Paul Comerford, author, unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved.